You have to admit that fresh borlotti beans are very pretty. They are also quite hard to find. Maybe that will change. It seems rather quaint now to read Elizabeth David’s advice in her book on Italian Food on how to obtain that rare and exotic vegetable, the courgette.

I hope borlotti beans don’t go quite the same way: for now, fresh ones are still unusual enough in England that it’s a special occasion when I can buy some from the farmers’ market, or find a few in a veggie box from Valvona & Crolla. Finding courgettes doesn’t have the same effect. I was quite pleased the first time I bought some courgette flowers locally, but making a meal with them reminded me of the orchid scene in Barbarella.

Beans are rather more substantial, and last week I was lucky enough to spot some at the farmers’ market. I suppose that if they start to appear more regularly, I’ll have to find a few different ways to cook them, but while I can only get them once or twice a year, I’ll stick with Marcella Hazan’s recipe for Assunta’s beans (from her book, Marcella Cucina).

Beans are rather more substantial, and last week I was lucky enough to spot some at the farmers’ market. I suppose that if they start to appear more regularly, I’ll have to find a few different ways to cook them, but while I can only get them once or twice a year, I’ll stick with Marcella Hazan’s recipe for Assunta’s beans (from her book, Marcella Cucina).

It’s a very simple recipe: shell the beans, put them in a pan with a few cloves of garlic, a handful of sage leaves, salt, pepper, a good glug of olive oil and a bit of water. Cover the pan and simmer for one and a half to two hours.

You can eat the beans just as they are, or put them on toast. You could add tuna (Marcella approves!) to make a sort of warm version of tonno e fagioli, but I prefer them without, because you lose the clarity of flavour by mixing the beans with fish. It works best as a lightish lunch or a fairly substantial starter in the context of an English-style meal.

Unfortunately, the cooked beans are not especially pretty, because the pink and white turns to light brown, but they taste wonderful, and aren’t likely to be around for long anyway.

After a seemingly endless succession of tasteless figs, peaches, pears etc one starts to wonder if it’s worth bothering to keep trying. Today’s veggie box from Valvona & Crolla restored my optimism. The figs weren’t as pretty as the purple supermarket ones. They were green and a bit mushy. But they tasted sweet and figgy and were good enough to eat on their own without needing any culinary artifice. So I had a few like that. Then I had some more with prosciutto and a slice of Poilâne miche. And then a tiny espresso.

After a seemingly endless succession of tasteless figs, peaches, pears etc one starts to wonder if it’s worth bothering to keep trying. Today’s veggie box from Valvona & Crolla restored my optimism. The figs weren’t as pretty as the purple supermarket ones. They were green and a bit mushy. But they tasted sweet and figgy and were good enough to eat on their own without needing any culinary artifice. So I had a few like that. Then I had some more with prosciutto and a slice of Poilâne miche. And then a tiny espresso.

They sent some peaches too, but I haven’t tried them yet. Also peppers, aubergine, chillis, Scottish strawberries, chanterelles and tomatoes. There was some prosciutto, cheese, salami and olive oil too.

I’m feeling very contented.

Yesterday’s experiments with figs made me think of the systematic approach to cooking peas that is presented in Mastering the Art of French Cooking. At the start of six pages on the subject, the authors apologise that, “we have not the space in this book to cover every aspect of pea cookery…” I’d be interested to know what aspects of pea cookery they feel they missed. Certainly there are plenty of pea recipes that aren’t included, but they give a very useful framework for making the most of your peas.

If you have perfect young, sweet, tender peas, then your job as cook is very easy. Keep it simple and let the peas speak for themselves. A brief blanching, some butter, and a little salt and pepper are all that’s needed. Actually, the Mastering team adds a tablespoon of sugar to their half pound of petit pois and to all the subsequent recipes, but I think they’re better without it.

As the peas become bigger, older, more mealy and less sweet, the cook needs to give them progressively more assistance:

- If the peas are bigger, but still quite young and sweet, boil them until they’re almost cooked, then drain them and finish them by cooking slowly in butter with salt, pepper and chopped mint.

- As the peas get a bit older, finely chopped shallot added with the butter in the final stage will give a little more sweetness and moistness. (Frozen peas get this treatment together with some chicken stock to boost the flavour.)

- Large tough peas are put in a pan with enough water to cover by ¼”and boiled for 20-30 minutes with the extras: chopped spring onion, butter, salt and pepper and the secret ingredient, shredded lettuce. Yes, it really works.

Of course, it’s useful to have detailed instructions on how to deal with any kind of pea you might encounter (there’s even advice for tinned peas) but the real lesson here is about seeing how much you need to add to your ingredients. When you’re lucky enough to get the best, your skill is to recognise it and leave it alone. When your ingredients are less than the best, then it’s time for you to add some culinary magic.

Here are a few ideas for those times when you feel nature needs a little assistance:

Tomato salad – the best just need olive oil, and a little salt. Henry Harris’s tomato and preserved lemon salad is wonderful for the others. Mix together ground cumin, chopped garlic, oregano, olive oil, red wine vinegar and salt – enough for a generous dousing of your tomatoes. Slice the tomatoes, a couple of wedges of preserved lemon, and some red onion. Scatter the onion and lemon over the tomatoes, pour the dressing over it all, and let it stand for an hour or two before you eat it. Your serving dish will probably have a tomato juice & dressing mixture left at the end, which you can save for your next salad.

Peaches – again, the best don’t need your help. The rest are good peeled, cut into wedges, and marinaded in slightly sweetened campari and orange juice (about 1 Tbsp of each per peach).

Strawberries – it sounds unlikely, but dull strawberries perk up no end if you toss them with a little balsamic vinegar. A very little is enough to boost the flavour without being obtrusive. Apparently in the Renaissance serving pepper with your strawberries was popular. I haven’t tried that yet.

I once had a plate of wonderful figs. They were deep purple, with juicy pink insides and perfect sweetness and figginess. Very many times I have had figs that ranged from indifferent downwards. They look so pretty in the shop: purple and plump. But it’s very rare (at least in England) to find much flavour.

So what do you do when the memory of that long ago figgy perfection was called forth at the sight of this season’s supermarket offering, and you find yourself at home with a bowl of tasteless but beautiful fruit?

If the figs are half decent, then you could try eating them with a plate of prosciutto, so that the emphasis is on the ham and the pairing of flavours not just the fig. Figs are good with soft, creamy cheese, too, and if necessary you can add a little light floral or herbal honey to compensate for the lack of sweetness in the fruit, though you risk drowning out their flavour altogether. Walnuts and manchego cheese could be good to, but the truth is that these classical pairings really work best when the figs have enough flavour to match the foods they’re paired with.

With the quality of fig most of us have access to, drastic measures are called for. Deborah Madison is very clever with flavours: she pairs figs with caramelised sugar, orange flower water and cream. It won’t create fig flavour when you didn’t have any to start with, but your lucky guests will probably clean their plates very happily anyway.

Pour some sugar onto a plate. Cut your figs in half, and dip the cut side in the sugar, then put the figs, cut side down, in a hot cast iron frying pan (if you don’t have one of these, you need one). Let the sugar melt and sizzle for a minute or two, then turn the figs over for a minute. Remove them from the pan to your serving dish, turn off the heat, pour some double cream into the pan, and stir it to dissolve the sugar. Add a teaspoon or two of orange flower water, pour the sauce over the figs and serve.

If you want something even simpler, just cut the figs in half, sprinkle the cut side with sugar and put them under the grill until the sugar melts and they start to brown. These would go well with cream, mascarpone, ice cream …

Sadly, they still won’t taste like the perfect figs you remember from long ago. Maybe next time.

Fernand Point had three Michelin stars for decades and he trained a good proportion of all the French chefs who have had three stars since his time (he died in 1955). So why had I not heard of him until last week?

I came across a translation of his writings, printed together with a few chapters about the man and his restaurant (La Pyramide near Lyons). As you might imagine, cooking that collected so many stars isn’t necessarily suitable for the home kitchen. Not least because few of us have ready access to apparently limitless supplies of foie gras and truffles! Point didn’t suffer such any limitations, and he seems to have made full use of the opportunity to consume fine food and wine. What makes the book so fascinating is not just the recipes, which are fairly sketchy (he described them as “abbreviations for the working cuisinier”) but the larger than life person who still comes through so vividly more than fifty years after his death.

Apparently he started his breakfast each day with two magnums of Champagne at about 9am, while being shaved (he got up at 4:30, so his day was well underway by nine). “I like to start off my day with a glass of Champagne,” he said. “I like to wind it up with Champagne too. To be frank, I also like a glass or two in between.” His morning included the necessary preparations for serving lunch, and meticulous attention to all the details of food purchase, preparation and serving that are crucial to getting and keeping your Michelin stars, while consuming three chickens or so, washed down with more Champagne.

As well as collecting recipes, Point used to jot down thoughts or quotations that struck him:

Butter! Give me butter! Always butter!

Butter! Give me butter! Always butter!

That which is very simple is not necessarily the least delectable. Take, for instance, sauerkraut. Yet, you still have to know how to prepare it.

After a cocktail or, worse yet, two, the palate can no more distinguish a bottle of Château Mouton-Rothschild from a bottle of ink!

If the divine creator has taken pains to give us delicious and exquisite things to eat, the least we can do is prepare them well and serve them with ceremony.

There are many people who claim to be good cooks; just as there are many people who, after having repainted the garden gate, take themselves to be painters.

When I stop in a restaurant I don’t know. I always ask to shake hands with the cuisinier before the meal. I know if he is thin, I’ll probably eat poorly. And if he is both thin and sad, the only hope is in flight.

Cookbooks are as alike as brothers. The best one is the one you write yourself.

I have been so well nurtured throughout my life that I’m sure to die completely cured.

Here’s a sample recipe from the book, Ma Gastronomie:

Coq en pâte Antonin Carême

Prepare a forcemeat consisting of equal quantities by weight of chicken livers and foie gras. Bind the forcemeat with a whole egg, add a little Madeira wine and some diced truffles. Season a nice plump rooster and stuff it with the forcemeat. Roast the bird about thirty minutes and let it cool a little. Cover it with a pastry dough and put it in the oven for at least an hour. Serve the rooster with a very good sauce Périgueux, along with a julienne of truffle.

Definitely a man with style!

That which is very simple is not necessarily the least delectable. Take, for instance, sauerkraut. Yet, you still have to know how to prepare it.

Most of the piccalilli recipes I’ve seen agree on one thing. It doesn’t much matter which vegetables you use as long as cauliflower is one of them. Often when recipes leave the choice of vegetables or herbs to the individual cook, it’s because various combinations will create different, but equally acceptable effects. In the case of piccalilli, it’s because, underneath all that mustard, it’s pretty much impossible to taste the separate vegetable flavours.

Normally when I cook, I consider appearance as important, but secondary to the flavour. In choosing piccalilli ingredients, as long as there’s some crunch in the bits, the appearance becomes more important than the flavour. I like to see some green, so I’ll use either cucumber or courgette as well as some green beans. Carrot adds a few bits of orange, then some neutral can come from parsnip or celeriac. Tiny silverskin onions would be nice, but I rarely manage to find any, and they’d be very fiddly to peel, so I’ve generally used pickling onions or shallots and cut them into four. Sometimes the bits stay together and sometimes they don’t. It doesn’t seem to make much difference.

It seems that various forms of “Indian Pickle” were becoming popular during the 18th century. Hannah Glasse didn’t have a recipe for it in the first edition of her book in 1747, but she added one to the fifth edition in 1755. Elizabeth Raffald’s version in The Experienced English Housekeeper, 1769 is more similar to modern ones, and includes cabbage, cauliflower, cucumber, “raddish pods”, kidney beans and beetroot or “any other thing you commonly pickle.”

Sadly, piccalilli isn’t very fashionable these days, and when I mention it, there’s rarely any enthusiasm in the response. I have noticed, though, that if a jar is put on the table, it is usually empty by the end of the meal. It goes well with cold meat, pork pie, sausages, or in a cheese sandwich. Many of the more modern authors seem to have decided that adding sugar is a good idea. It isn’t. The recipe below is more or less based on the version given by Nick Sandler and Johnny Acton in their book, “Preserved,” (one of the few that doesn’t add half a pound of sugar).

Sadly, piccalilli isn’t very fashionable these days, and when I mention it, there’s rarely any enthusiasm in the response. I have noticed, though, that if a jar is put on the table, it is usually empty by the end of the meal. It goes well with cold meat, pork pie, sausages, or in a cheese sandwich. Many of the more modern authors seem to have decided that adding sugar is a good idea. It isn’t. The recipe below is more or less based on the version given by Nick Sandler and Johnny Acton in their book, “Preserved,” (one of the few that doesn’t add half a pound of sugar).

Ingredients

1 kg/good 2 lbs vegetables (including cauliflower plus others as you choose)

2 Tbsp salt

1 Tbsp turmeric

50g/2oz mustard powder (yes, really!)

½ tsp ground white pepper

50g/2oz plain flour

¼ tsp ground nutmeg

250 ml/8 fl oz cider vinegar

250ml/8 fl oz malt vinegar

Break the cauliflower into small florets and cut the remaining vegetables into small dice (about ¼”). Mix in the salt, cover the bowl, and leave them overnight.

Mix the spices, flour and 80ml/3 fl oz cider vinegar until it’s smooth. Slowly stir in the rest of the cider vinegar, pour it into a large saucepan, and add the vegetables and malt vinegar. Heat it gently until the sauce starts to simmer. Add a little water if the sauce seems too thick. If you want the vegetables to be soft, you can continue to cook it for a few minutes, but I like to remove it from the heat as soon as it reaches simmering.

Pour the piccalilli into sterilised jars. This quantity will make about three 300ml/12 oz jars.

Sir Basil likes a biscuit with his tea. The latest batches have been gingernuts. When I first searched the internet for a recipe, I was surprised to find they seem to have quite a cult following. A very small, well-behaved cult, but still… The enthusiasts like their gingernuts hard. If you don’t dunk them, you risk breaking a tooth. There is a certain appeal to such robust biscuits, but they’re not what you want on every occasion. I finally found a recipe that produces a crunchy, but not hard biscuit, hiding in a Delia Smith book that I’ve had for more than 20 years. I’m not too good at following instructions, so I’ve changed a few things. Here are the two versions (Sir Basil likes the hard ones). Both recipes make about 30 biscuits.

Sir Basil likes a biscuit with his tea. The latest batches have been gingernuts. When I first searched the internet for a recipe, I was surprised to find they seem to have quite a cult following. A very small, well-behaved cult, but still… The enthusiasts like their gingernuts hard. If you don’t dunk them, you risk breaking a tooth. There is a certain appeal to such robust biscuits, but they’re not what you want on every occasion. I finally found a recipe that produces a crunchy, but not hard biscuit, hiding in a Delia Smith book that I’ve had for more than 20 years. I’m not too good at following instructions, so I’ve changed a few things. Here are the two versions (Sir Basil likes the hard ones). Both recipes make about 30 biscuits.

Hard Gingernuts

4 oz brown sugar

2 oz treacle

3 oz butter

1/2 tsp bicarb

8 oz plain flour

2 tsp ground ginger

1/2 tsp cinnamonPreheat the oven to 160°C/315°F.

Melt the butter, treacle and sugar together. Add the bicarb. Stir in the flour and spices. Form into walnut-sized balls, and flatten them a bit. Bake for 15 mins. Cool on a wire rack, then store in an airtight tin.

I’m not sure of the source of this recipe, but I can confirm that it makes a very robust biscuit, ideal for dunking.

Crunchy Gingernuts

8 oz plain flour

1/2 tsp baking powder

1 tsp bicarbonate of soda

2 tsp ground ginger

4 oz butter

3 oz soft brown sugar

2 oz molasses or treaclePreheat the oven to 190°C/375°F.

Mix the flour, baking powder, bicarbonate and ginger together. Rub in the butter, as if you were making pastry, until the mixture is crumbly. Add the treacle and mix to form a stiff paste. Form it into walnut sized balls. Put them on a baking sheet, flatten them slightly, and bake for 10 – 15 minutes. Cool them on the baking sheet for ten minutes, then transfer to a wire rack to cool completely. Store in an airtight tin.

As you can see, the ingredients are very similar. I think that what makes the two versions so different, is incorporating the flour in a hot or a cold mix. The flavour was a little richer with the top recipe, but adding a little cinnamon to the ginger in the second one would probably change that. Next time…

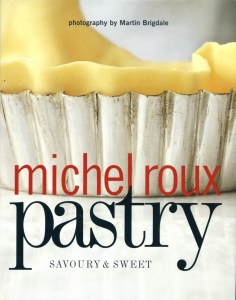

I don’t often see how other people cook. I don’t watch television; I do most of the cooking at home. I’ve even been known to take over my hosts’ kitchen when staying with my family. I like to read cookery books, but there aren’t many cooks I’d go out of my way to see. One of that small group was promoting a new book recently, so I grabbed the chance to watch Michel Roux demonstrating a couple of recipes from his new book, Pastry, a return to his roots for someone who started work in a bakery in Paris 50-odd years ago as a fourteen year old.

Michel Roux has had multiple Michelin stars for decades, and one of my very first cookery books was The Roux Brothers on Patisserie (written jointly with his brother, Albert), which has been my reference for pastry and various associated sauces for 20+ years.

Michel Roux has had multiple Michelin stars for decades, and one of my very first cookery books was The Roux Brothers on Patisserie (written jointly with his brother, Albert), which has been my reference for pastry and various associated sauces for 20+ years.

For the demonstration, Roux cooked two recipes from the new book: a savoury “semi-confit tomato” tart using shortcrust pastry, and a sweet apple and passion fruit tartlet that uses puff pastry in the book, but for which he substituted rough puff in the demonstration, explaining that it gives you 80% of the effect of puff pastry for a lot less work, and that it’s perfectly adequate almost all the time for home cooks.

Roux is a natural entertainer. He borrowed a flowered apron from one of the bookshop staff serving lunch at the event, the pink flowers clashing loudly with his burgundy shirt. He explained that recipes weren’t to be followed slavishly, but taken as a starting point, and that tips and techniques were more useful than recipes. The tips that he passed on in this lunchtime talk ranged from damping the baking tray to fix the rough puff pastry circles in place to announcing that he was about to blow his nose because allowing your nose to drip into the pastry was not a good thing. The demonstration – and the book – were aimed more at home cooks than restauranteurs. Although some of the recipes are certainly impressive enough, the main message is that making pastry isn’t at all difficult. It tastes and smells wonderful, and is well worth making at home.

Some of what he said was obvious to most home cooks, but not always to restauranteurs: food must taste good. While waiting in a queue afterwards to get my book signed, I was able to taste the tarts he’d made. They did taste good. And they hadn’t taken a lot of time, effort or fancy equipment.

The recipes in Pastry look fine, and cover homely English pasties and pies along with fancy French pastries, but I already have lots of recipes and agree with Roux that they’re not really the important thing, so I don’t see that they’ll be especially useful for me. What was worth while was watching Roux’s ease with the pastry, and his blank bafflement when asked about pastry shrinking during cooking. Clearly his pastry wouldn’t dare to do such a thing – and certainly the ones he cooked that day kept their shape perfectly. If you’re not used to making pastry, and want a book that will get you started while having enough recipes and variety to last you for years, you could do a lot worse than this one.

Some of the recipes in Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery, made Plain and Easy seem to come from another world. So much has changed in the 260 years since she was writing that the many of the recipes seem bizarre and most of us would have no idea how to combine them to produce a coherent meal. Some recipes use birds or fish that aren’t commonly eaten these days, or use bits of them that we’re not used to eating (there are three different ways to cook a cod’s head, for instance). Some have combinations of sweet and savoury that look strange these days: like sprinkling sugar over your potatoes.

It’s a surprise, in the midst of this alien world, to come across a recipe that is still in common use, pretty much unchanged.

To make Common Saufages.

Take three Pounds of nice Pork, Fat and Lean together, without Skin or Grifles; chop it as fine as poffible, feafon it with a Tea Spoonful of beaten Pepper, and two of Salt, fome Sage fhread fine, about three Tea Spoofuls; mix it well together, have the Guts very nicely cleaned, and fill them, or put them down in a Pot, so roll them of what Size you pleafe, and fry them. Beef makes very good Saufages.

For “fine sausages,” she recommends using only lean pork, and substituting beef suet for the fat (using equal quantities of pork and suet), and adding sweet herbs, nutmeg and lemon zest to the seasoning.

Of course, sausages are much older than the 18th century. They were certainly around in Roman times, though the fact that the latin name for sausages is the origin of the word “botulism” suggests it would have been wise to approach them with some caution.

It’s quite possible that even in Glasse’s day those who were less wealthy than her readers might have added some cereal to the mix. These days, some sausages, like Glasse’s, are made with just meat and seasonings, while others have substantial cereal additions. Walls sausages for instance contain about 65% meat, with water and rusk making up the bulk of the remainder.

I’ve experimented with various formulae, and finally decided that just a little bread improves the sausage texture and helps it to stay juicy when it’s cooked. I use pork shoulder, and try to get a moderately fatty piece. If there isn’t much fat, then I’ll add in some belly pork, or extra back fat (if you’re buying your meat from a butcher, he’ll probably have some he can spare). I also like a pretty traditional seasoning, but there’s plenty of scope for variation: rosemary and thyme; juniper; fennel…

For a couple of pounds of meat, I use:

1 1/2 oz breadcrumbs (about 5% of the weight of the meat)

1 Tbsp Maldon salt (the brand isn’t important, but the big flakes mean you don’t get so much in a tablespoon – if you’re using finely ground salt, use 2 tsp, or 1.5% of the weight of the meat)

Chopped sage – a handful

1/2 Tbsp ground mixed spice (about half black pepper, and the rest a mixture of nutmeg, mace, cinnamon, clove, allspice).

2 yards of hog casings (sheep casings give thinner, chipolata-size sausages)

Mince the meat. I prefer a coarse grind. Mix in the breadcrumbs and seasonings, then put the mixture through the mincer again. My mincer has an attachment for stuffing sausages. Basically, you remove the chopping plates, and add a funnel. Lubricate the outside of the funnel (butter or lard work pretty well). Thread the sausage casings onto the funnel, then feed the mixture through again, this time into the casing. Tie off the ends of the casing and twist the sausages to the length you want.

The sausages will be better if you can leave them for a day or two before cooking them. I put them on a plate in the fridge, covered with kitchen paper.

You could fry them and serve with mash and/or braised sauerkraut; braise them with beef stock, red wine and chestnuts; or combine them with another old English favourite, Yorkshire Pudding, to make Toad in the Hole.