You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘Cooks’ category.

Fernand Point had three Michelin stars for decades and he trained a good proportion of all the French chefs who have had three stars since his time (he died in 1955). So why had I not heard of him until last week?

I came across a translation of his writings, printed together with a few chapters about the man and his restaurant (La Pyramide near Lyons). As you might imagine, cooking that collected so many stars isn’t necessarily suitable for the home kitchen. Not least because few of us have ready access to apparently limitless supplies of foie gras and truffles! Point didn’t suffer such any limitations, and he seems to have made full use of the opportunity to consume fine food and wine. What makes the book so fascinating is not just the recipes, which are fairly sketchy (he described them as “abbreviations for the working cuisinier”) but the larger than life person who still comes through so vividly more than fifty years after his death.

Apparently he started his breakfast each day with two magnums of Champagne at about 9am, while being shaved (he got up at 4:30, so his day was well underway by nine). “I like to start off my day with a glass of Champagne,” he said. “I like to wind it up with Champagne too. To be frank, I also like a glass or two in between.” His morning included the necessary preparations for serving lunch, and meticulous attention to all the details of food purchase, preparation and serving that are crucial to getting and keeping your Michelin stars, while consuming three chickens or so, washed down with more Champagne.

As well as collecting recipes, Point used to jot down thoughts or quotations that struck him:

Butter! Give me butter! Always butter!

Butter! Give me butter! Always butter!

That which is very simple is not necessarily the least delectable. Take, for instance, sauerkraut. Yet, you still have to know how to prepare it.

After a cocktail or, worse yet, two, the palate can no more distinguish a bottle of Château Mouton-Rothschild from a bottle of ink!

If the divine creator has taken pains to give us delicious and exquisite things to eat, the least we can do is prepare them well and serve them with ceremony.

There are many people who claim to be good cooks; just as there are many people who, after having repainted the garden gate, take themselves to be painters.

When I stop in a restaurant I don’t know. I always ask to shake hands with the cuisinier before the meal. I know if he is thin, I’ll probably eat poorly. And if he is both thin and sad, the only hope is in flight.

Cookbooks are as alike as brothers. The best one is the one you write yourself.

I have been so well nurtured throughout my life that I’m sure to die completely cured.

Here’s a sample recipe from the book, Ma Gastronomie:

Coq en pâte Antonin Carême

Prepare a forcemeat consisting of equal quantities by weight of chicken livers and foie gras. Bind the forcemeat with a whole egg, add a little Madeira wine and some diced truffles. Season a nice plump rooster and stuff it with the forcemeat. Roast the bird about thirty minutes and let it cool a little. Cover it with a pastry dough and put it in the oven for at least an hour. Serve the rooster with a very good sauce Périgueux, along with a julienne of truffle.

Definitely a man with style!

That which is very simple is not necessarily the least delectable. Take, for instance, sauerkraut. Yet, you still have to know how to prepare it.

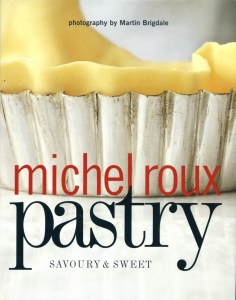

I don’t often see how other people cook. I don’t watch television; I do most of the cooking at home. I’ve even been known to take over my hosts’ kitchen when staying with my family. I like to read cookery books, but there aren’t many cooks I’d go out of my way to see. One of that small group was promoting a new book recently, so I grabbed the chance to watch Michel Roux demonstrating a couple of recipes from his new book, Pastry, a return to his roots for someone who started work in a bakery in Paris 50-odd years ago as a fourteen year old.

Michel Roux has had multiple Michelin stars for decades, and one of my very first cookery books was The Roux Brothers on Patisserie (written jointly with his brother, Albert), which has been my reference for pastry and various associated sauces for 20+ years.

Michel Roux has had multiple Michelin stars for decades, and one of my very first cookery books was The Roux Brothers on Patisserie (written jointly with his brother, Albert), which has been my reference for pastry and various associated sauces for 20+ years.

For the demonstration, Roux cooked two recipes from the new book: a savoury “semi-confit tomato” tart using shortcrust pastry, and a sweet apple and passion fruit tartlet that uses puff pastry in the book, but for which he substituted rough puff in the demonstration, explaining that it gives you 80% of the effect of puff pastry for a lot less work, and that it’s perfectly adequate almost all the time for home cooks.

Roux is a natural entertainer. He borrowed a flowered apron from one of the bookshop staff serving lunch at the event, the pink flowers clashing loudly with his burgundy shirt. He explained that recipes weren’t to be followed slavishly, but taken as a starting point, and that tips and techniques were more useful than recipes. The tips that he passed on in this lunchtime talk ranged from damping the baking tray to fix the rough puff pastry circles in place to announcing that he was about to blow his nose because allowing your nose to drip into the pastry was not a good thing. The demonstration – and the book – were aimed more at home cooks than restauranteurs. Although some of the recipes are certainly impressive enough, the main message is that making pastry isn’t at all difficult. It tastes and smells wonderful, and is well worth making at home.

Some of what he said was obvious to most home cooks, but not always to restauranteurs: food must taste good. While waiting in a queue afterwards to get my book signed, I was able to taste the tarts he’d made. They did taste good. And they hadn’t taken a lot of time, effort or fancy equipment.

The recipes in Pastry look fine, and cover homely English pasties and pies along with fancy French pastries, but I already have lots of recipes and agree with Roux that they’re not really the important thing, so I don’t see that they’ll be especially useful for me. What was worth while was watching Roux’s ease with the pastry, and his blank bafflement when asked about pastry shrinking during cooking. Clearly his pastry wouldn’t dare to do such a thing – and certainly the ones he cooked that day kept their shape perfectly. If you’re not used to making pastry, and want a book that will get you started while having enough recipes and variety to last you for years, you could do a lot worse than this one.

“It cannot be denied that an improved system of practical domestic cookery, and a better knowledge of its first principles, are still much needed in this country,” said Eliza Acton, writing in 1845. That (and the fact that her publisher turned down the book of poems she’d written, and said he’d prefer a cookery book) was what prompted Acton to write Modern Cookery for Private Families. The statement is probably just as true today as it was when she wrote it, but these days every book shop food section bulges with more cookery books than one person could ever use in a lifetime. The reluctant cook has a seemingly limitless supply of restaurants to choose from, and there are ready made meals to reheat for a night at home. So why is Eliza Acton’s book still in print?

The recipes are good. They’re thoroughly tested, clearly written, and they work. Not all modern books can say the same. But that’s probably not enough to earn a 160 year old book a place on your kitchen shelf. I think that what keeps the book alive is that when you read these recipes, you want to read them aloud. Eliza Acton may not have been a great poet, but she wrote prose that just begs to be spoken. Her recipes are as satisfying to read as they are to cook and to eat.

It’s easy to get the impression of a maiden aunt kind of figure: very organised, precise, and respectable. But Miss Acton does have a somewhat racy past. It seems that not only did she write poetry, but she spent much of her youth in France, where she was engaged to a young French officer. The engagement was broken off when she found out that he had been unfaithful, but there were rumours that she had a daughter by him, who was brought up by one of her sisters.

Here’s one of her steak pudding recipes. You can make this with packet suet from the supermarket, but it will be incomparably lighter and better tasting if you get some fresh suet. I’ve found that farmers’ markets or farm shops are the places you’re most likely to find it.

SMALL BEEF-STEAK PUDDING

Make into a very firm smooth paste, one pound of flour, six ounces of beef-suet finely minced, half a teaspoonful of salt, and half a pint of cold water. Line with this a basin which holds a pint and a half. Season a pound of tender steak, free from bone and skin, with half an ounce of salt and half a teaspoonful of pepper well mixed together; lay it in the crust, pour in a quarter of a pint of water, roll out the core, close the pudding carefully, tie a floured cloth over, and boil it for three hours and a half. We give this receipt in addition to the preceding one, as an exact guide for the proportions of meat puddings in general.

Flour, 1 lb.; suet, 6 oz.; salt, ½ teaspoonful; water ½ pint; rumpsteak, 1 lb.; salt, ½ oz.; pepper ½ teaspoonful; water, ¼ pint; 3½ hours.

The idea of summarising the recipe at the end was a novel one, introduced by Eliza Acton. A few years later, Isabella Beeton copied the idea, but moved the list to the start of the recipe, setting the format that’s in more or less universal use today.